When a 'Good Latch' Feels Bad: Understanding What’s Really Going On

Has someone told you, “Your latch looks good,” but deep down, you feel like something isn’t right? Maybe feeding still hurts, your baby isn’t gaining enough weight, or it just feels like feeding shouldn’t be this hard. If that sounds familiar, trust your instincts—this post is for you.

It’s natural to second-guess yourself when things don’t feel right. Maybe you’ve thought, “Is it just me? Am I doing something wrong?” Or even, “If I could just remember what they showed me in the hospital, I’d have this figured out by now.”

But here’s the truth: It’s not your fault. You’re not doing anything wrong. And you are enough.

What Is Latching?

Latching is how your baby attaches to your chest or breast to initiate the flow of milk. This process works by creating a vacuum inside their mouth, and there are two main ways your baby might do this:

- Suction-Driven Latch: Your baby uses suction, like drinking from a straw.

- Lift-Driven Latch: Your baby uses their tongue to lift and lower, creating a vacuum.

While both methods can remove milk, a lift-driven latch is better for feeding and comfort. It’s more efficient, feels better for you, and helps your baby build stronger oral muscles. This type of latch creates what’s called a functional vacuum.

On the other hand, a suction-driven latch is compensatory. It doesn’t work as effectively and often requires your baby to overuse other muscles to keep milk flowing. This can lead to frustration for both of you.

To make things more complex, your baby doesn’t always rely on just one method. They might use a combination of suction and lift to help milk flow, which can vary from feed to feed.

Forget “Good” or “Bad” Latch

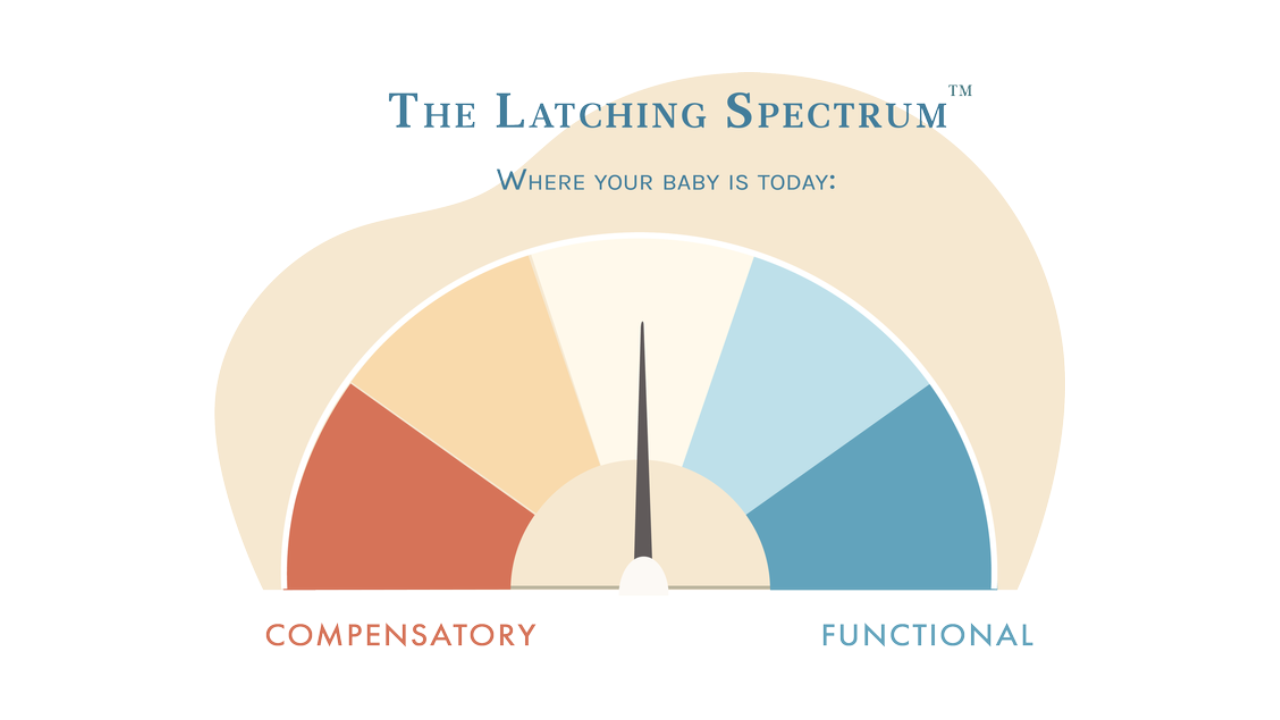

A latch isn’t simply “good” or “bad.” Instead, it falls somewhere on a latching spectrum—ranging from purely suction-driven to purely lift-driven.

The closer your baby is to the suction-driven side, the more compensatory behaviors they may rely on to make up for inefficiencies. These behaviors can show up as:

- Clicking sounds while feeding

- Milk leaking from their mouth

- A shallow latch that feels painful

On the other hand, functional feeding behaviors include:

- A deep, comfortable latch

- Efficient milk transfer

- A content baby after feeding

Most babies fall somewhere in the middle, using a mix of functional and compensatory behaviors during feeds, and this can be hard to spot unless you know what to look for. This is why parents are often told their latch "looks good," even when their baby is showing subtle signs of compensation. These compensatory behaviors can go unnoticed but may still make feeding harder for both you and your baby.

Why This Matters

When we only focus on pain or weight gain to judge feeding success, we miss other important clues. Babies can struggle with feeding even when there’s no pain or weight loss because compensations make feeding harder for them.

The next time you feed your baby, take a closer look. Do you notice any of these signs?

- Chewing instead of sucking

- Passively feeding without actively drinking milk

- Coming unlatched easily during feeding

These are signs your baby might be relying on compensatory behaviors. Understanding this can help you take the first steps to make feeding easier for both of you.

How to Help Your Baby Feed Better

If you notice compensations, here are simple steps to try:

- Positioning Matters: Support your baby’s head and neck so they’re gently tilted back. This helps them use their tongue better.

- Feed Before Hunger Peaks: Offering milk before your baby gets upset helps them focus on latching calmly.

- Body Tension: Tension in your baby’s body can affect feeding. Bodywork, like seeing a pediatric chiropractor, can help.

If these adjustments don’t help, your baby might need more support. An IBCLC (lactation consultant) trained in oral function can help uncover what’s preventing a better latch.